Introduction

This analysis examines the case of the State of Oregon v. Pittman as well as the underlying legal questions concerning individual privacy rights in the digital age brought up by the case. Specifically, whether an individual can be legally required to unlock a smartphone is the central dispute in the State of Oregon v. Pittman. Furthermore, addressing this question requires exploring related underlying legal and ethical issues. Central among these are whether a right to privacy exists (or should exist) protecting individuals from compelled access to smartphone data, and the legal and ethical implications of potentially requiring tech companies to create bypass mechanisms for law enforcement access.

Furthermore, the legal and ethical questions raised by the Oregon v. Pittman case were not unique as similar cases, such as the predating “Apple v. FBI”² grappled with similar issues. Moreover, cases in this domain (Oregon v. Pittman, Apple v. FBI, Seo v. State, etc.) illuminate a historic issue, i.e., weighing individual privacy rights against government/communal safety concerns.

Analysis

The central question of whether existing law sufficiently protects individual rights when law enforcement seeks access to data on mobile devices is important because it touches on essential legal and ethical questions revolving around weighing individual privacy rights against governmental/communal safety concerns. Specifically, the case illuminates a gray area of law concerning what the unlocking of a device discloses, and whether that disclosure is constitutionally protected by laws protecting individuals’ rights.

Furthermore, taking a wider view, if the government could force individuals to unlock their smartphones, then the security of the smartphone (and similar devices) would be degraded, and therefore the privacy of the individual whose device was accessed would be significantly harmed. To that point, once the security of a device is compromised, i.e. an unwanted party has gained access to said information, the assurance of the preservation of the “confidentiality, integrity and availability”⁹ of the information stored on the device will have been greatly diminished.

Why are These Questions Important?

These research questions are important because individual privacy rights have encountered a new domain due to the advancement of technology, necessitating greater clarity concerning individual privacy rights within this digital realm. To that point, the decisions of courts in cases such as Oregon v. Pittman (and Apple v. FBI, Seo v. State, etc.) will have lasting legal and ethical consequences for U.S. citizens as their right to privacy is challenged by the governments’ striving to fulfill its duty to protect its citizens, sometimes by means that overstep the bounds of the Constitution.

Furthermore, privacy can only be achieved by preserving the confidentiality, integrity, and availability (CIA) of information stored on a smartphone or similar device. Therefore, if government entities were to gain widespread access to individuals’ smartphones (and similar devices) the CIA of individuals’ data could not be assured. Not only would this likely go against the ethical principles on which the framers based the Constitution, but moreover, it would establish a legal precedent that would encourage the government to attempt to gain even more access to individuals’ private information such as “recording conversations or location tracking”¹⁰. Lastly, a device cannot be considered secure once a bypass tool has been introduced as it could be exploited by other entities besides the government such as rough actors, hackers, and/or other nations, etc.

Is There or Should There Be a Right to Privacy That Would Protect an Individual From Being Compelled to Allow Law Enforcement Access to Data Stored on a Smart Phone or Similar Device?

To begin, the question of whether there is a legally protected right to privacy afforded to all individuals in the U.S. is important because it forms the basis for determining if a government entity has the legal authority to require an individual to unlock their device. To that point, the ethical argument for a “right to privacy”¹² was first put forth by Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis in 1890, which suggested that privacy be defined as “the right to be let alone”¹². Furthermore, although not specifically mentioned in the Constitution, the concept of individual privacy rights was established as law in Griswold v. Connecticut where it was determined that the amalgamation of individual rights granted by “the First, Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Ninth Amendments”⁴ constituted an “implied right to privacy in the Constitution”⁴. Therefore, there is a right to privacy granted by the U.S. Constitution.

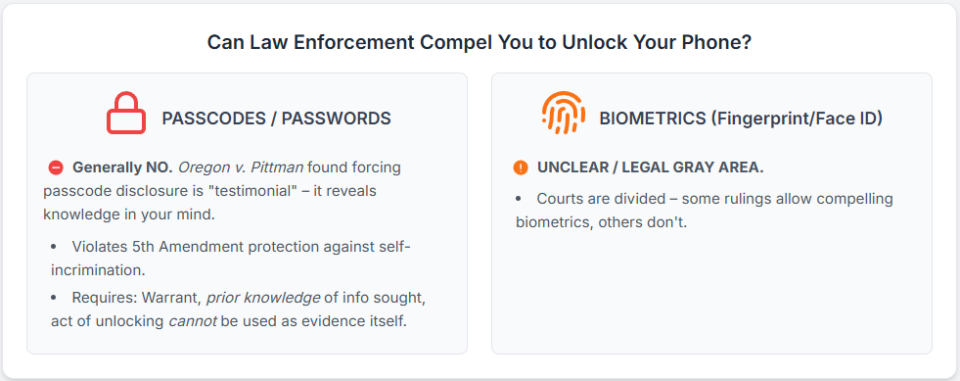

Furthermore, with regards to the State of Oregon v. Pittman, Oregon’s Supreme Court found that Oregon’s Constitution can force an individual to unlock their device so long as a warrant is issued and the state “(2) already knows the information that the act of unlocking the phone would communicate; and (3) is prohibited from using the defendant’s act against the defendant, except to obtain access to the contents of the phone”⁷. Point ‘3’ is of note as the ruling by the Oregon Supreme Court found that compelling the defendant to reveal their passcode was “testimonial”¹ in nature, which was defined as disclosing something “about a person’s beliefs, knowledge, or state of mind”⁷. Therefore, the Oregon Supreme Court found that it was unconstitutional to force a person to disclose the password as it would essentially be an act of testifying against themselves (self-incrimination), which is protected by both “Article I, section 12 of the Oregon Constitution and the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution”¹.

Moreover, since “the logic of the Pittman opinion could apply directly to other passcode-locked digital devices, including tablets, personal computers, and external hard drives”¹ and because privacy can only be achieved by preserving the confidentiality, integrity and availability of information stored on a smartphone or similar device; the Oregon Supreme Court ruling preventing law enforcement from forcing an individual to unlock their device helps to strengthen and preserve the CIA of data stored on all devices for all U.S. citizens. Moreover, The Supreme Court of Oregon’s ruling is consistent with rulings in similar cases as “most courts do find that the act of unlocking phones is a testimonial communication”¹³. However, it is important to note that the scope of this ruling was limited to passcodes/passwords, meaning that it is unclear at this time if biometric access features (facial scan, fingerprint) can be compelled by law enforcement. To that point, there have been rulings both for (Commonwealth v. Baust) and against (United States v. Wright) compelling biometrics from an individual to access their smartphone.

What are the Legal and Ethical Implications of Requiring Device Designers and/or Vendors to Provide Bypass Mechanisms to Allow Law Enforcement Agencies to Access Data Stored on Smart Devices?

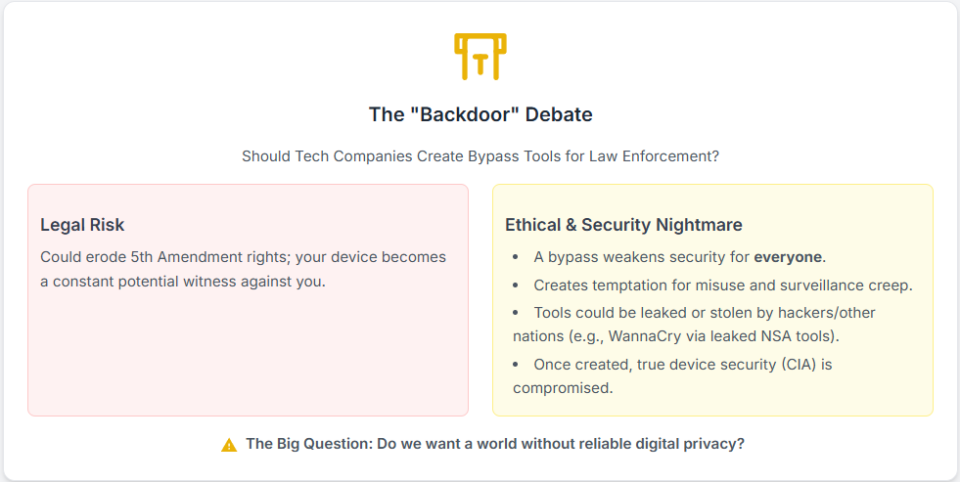

The legal and ethical questions raised in the State of Oregon v. Pittman are of the utmost importance as “A single smartphone can hold more data than all documents ever handwritten”¹, and much of that information directly corresponds to its user/owner. Therefore, precedents deciding the legality of compelling access to these devices are likely to be among the most consequential judicial rulings in the history of the United States. To that point, the legal implications of requiring bypass mechanisms are that individuals will be constantly creating a trail of evidence anytime they possess/use their smartphone (or similar device) that will later be used against them by the government in their prosecution. In practice, the result of such precedents would lead to an almost total eradication of the protections afforded to individuals by the 5th Amendment.

Moreover, the questions raised by Oregon v. Pittman are not limited to the realm of legality as there are also critical ethical questions raised by this and other similar cases, such as “Apple v. FBI”². To that point, if it becomes law that bypass mechanisms be created by device designers the following ethical dilemma will unfold. Once a backdoor and/or tool is created that could bypass the access security features of a device, the security (confidentiality, integrity, and availability) of that device is irreparably harmed. Meaning, that once an exploit is introduced of this magnitude, privacy can no longer be expected when using said device. Moreover, there will be an unavoidable temptation to use these tools in more and more situations, further eroding individual privacy. Lastly, threat actors will constantly be attempting to obtain this tool from wherever it is housed which will further imperil the ability of individuals to preserve their privacy. The potential for such a tool falling into the wrong hands cannot be underestimated as exemplified by the cases of the “WannaCry3 and Petya4 attacks, which were developed using the leaked Shadow Brokers exploit, EternalBlue, which is generally believed to have been developed by the US National Security Agency (NSA)”¹⁴.

Therefore, the introduction of bypass tools of this nature is an all-or-nothing proposition, i.e., either privacy is catered for absolutely by the makers of these devices, or it is not, and the information stored on makers of said devices will be left vulnerable. As a result, the primary ethical question that would be raised if the government could require companies to create bypass tools is, do we want to live in a world where privacy no longer exists?

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is an unprecedented amount of data stored on smartphones (and similar devices) that contains some of the most private information individuals possess. Moreover, individuals’ “right to privacy”¹² protects them from being forced to provide law enforcement their passcode/password (but maybe not their biometric features) thereby protecting device owners from providing “compelled, testimonial, and inculpatory”¹ evidence against themselves, which would violate the 5th Amendment¹. Furthermore, if it were decided that device creators were legally required to provide law enforcement with bypass mechanisms then the legal implication would be the government’s persistent use of individuals’ devices as witnesses against their owners, which would effectively end the ability of an individual to maintain their right to privacy. Meanwhile, the ethical implications of such a law would be creating a world where privacy no longer exists.

Therefore, the precedents set in Oregon v. Pittman and similar cases adjudicating law enforcement’s ability to force individuals to unlock their devices will effectively determine whether individuals will be able to maintain their constitutionally given “right to privacy”¹² in the digital age.

References

- DeMarco, J. (2021, April 23). State Court Docket Watch: State of Oregon v. Pittman. Fedsoc.org. https://fedsoc.org/commentary/publications/state-court-docket-watch-state-of-oregon-v-pittman#:~:text=In%20State%20v.%20Pittman%2C%20the%20Oregon%20Supreme%20Court

- Electronic Privacy Information Center. (n.d.). Apple v. FBI – EPIC – Electronic Privacy Information Center. Epic.org. https://epic.org/documents/apple-v-fbi-2/

- Cook, T. (2016, February 16). Customer Letter – Apple. Apple. https://www.apple.com/customer-letter/

- Cornell Law School. (n.d.). Privacy. LII / Legal Information Institute. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/privacy#:~:text=Eisenstadt%20v%20Baird%20(1971)%2C

- Crocker, A. (2020, June 23). Victory: Indiana Supreme Court Rules that Police Can’t Force Smartphone User to Unlock Her Phone. Electronic Frontier Foundation. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2020/06/victory-indiana-supreme-court-rules-police-cant-force-smartphone-user-unlock-her#:~:text=In%20the%20case%2C%20Seo%20v

- Maniam, S. (2016, February 19). Americans feel the tensions between privacy and security concerns. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2016/02/19/americans-feel-the-tensions-between-privacy-and-security-concerns/

- Supreme Court. (2021, January 28). Supreme Court: Media Release. Www.courts.oregon.gov. https://www.courts.oregon.gov/news/Lists/ArticleNews/Attachments/1414/3b02f5a371a6294c9f1a2aaaf1aa7349-1-28-21%20Opinion%20Media%20Release%20Final.pdf

- Vector. (2020). FBI vs. Apple — The Privacy Fight. [Video file]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rpz4xaX6YQw&t=399s

- Hashemi-Pour, C., & Chai, W. (2023, December). What is the CIA Triad? Definition, Explanation and Examples. TechTarget. https://www.techtarget.com/whatis/definition/Confidentiality-integrity-and-availability-CIA

- Apple. (n.d.). Customer Letter – FAQ – Apple. Apple. https://www.apple.com/customer-letter/answers/

- Valorie J., K., & J.D., D. (2022, June). Ethics and Ethical Decision Making. Learn.umgc. https://learn.umgc.edu/d2l/le/content/930351/viewContent/32124621/View

- Swire, P., & Kennedy-Mayo, D. (2020). U.S. private-sector privacy: law and practice for information privacy professionals (Third). International Association Of Privacy Professionals.

- Uresk, C. (2021). Compelling Suspects to Unlock Their Phones: Recommendations Compelling Suspects to Unlock Their Phones: Recommendations for Prosecutors and Law Enforcement for Prosecutors and Law Enforcement. BYU Law Review, 46(2). https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3288&context=lawreview

- Cooke, I. (2017, November 1). IS Audit Basics: Auditing Mobile Devices. ISACA. https://www.isaca.org/resources/isaca-journal/issues/2017/volume-6/is-audit-basics-auditing-mobile-devices